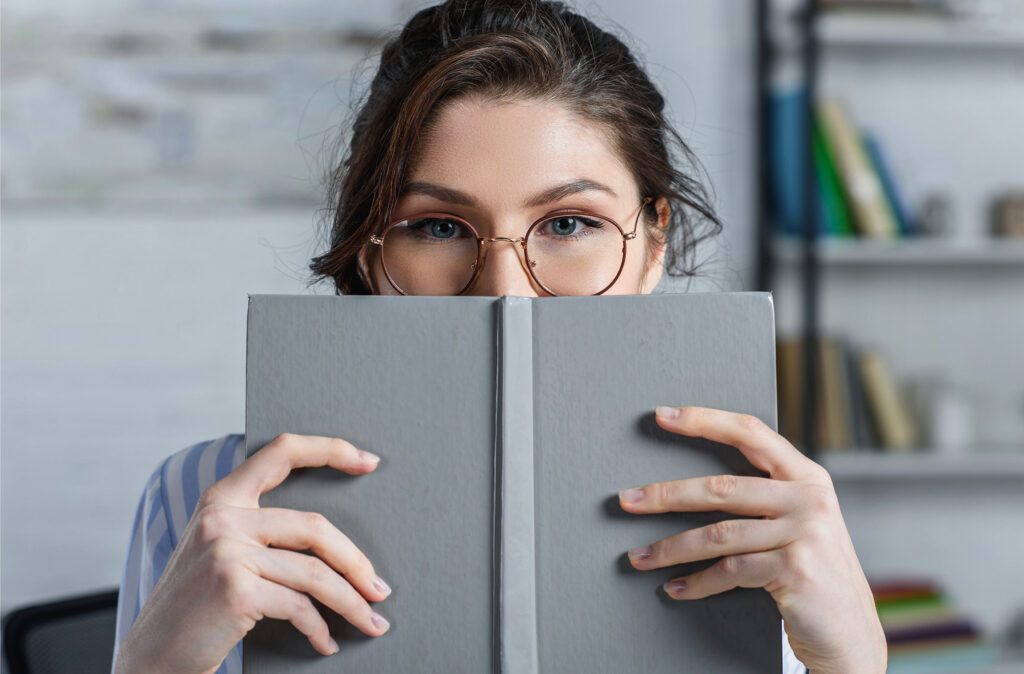

Anyone can do science – just not me!

Most young people see the STEM world as open to all. But many also struggle to see a place for themselves in it. IRIS tries to make sense of this seeming contradiction, and transform positive outlooks into personal ambitions.

In our survey of over 2,800 year 9 students, IRIS sought to measure young people’s attitudes towards STEM by asking whether they agreed or disagreed with a range of statements. Some of these statements were general: “anyone can do science”. Others were more personal: “people like me work in STEM”. Students’ responses to the two types of statement noticeably diverged. Consider some of the following contrasts:

- 61% of students agreed that “anyone can do science and be a scientist.” Even more convincingly, three quarters agreed that “STEM is for people from all backgrounds” (including 80% of the female students we surveyed)… but, when it came to personal identity, only 28% actually saw themselves as “a science person.”

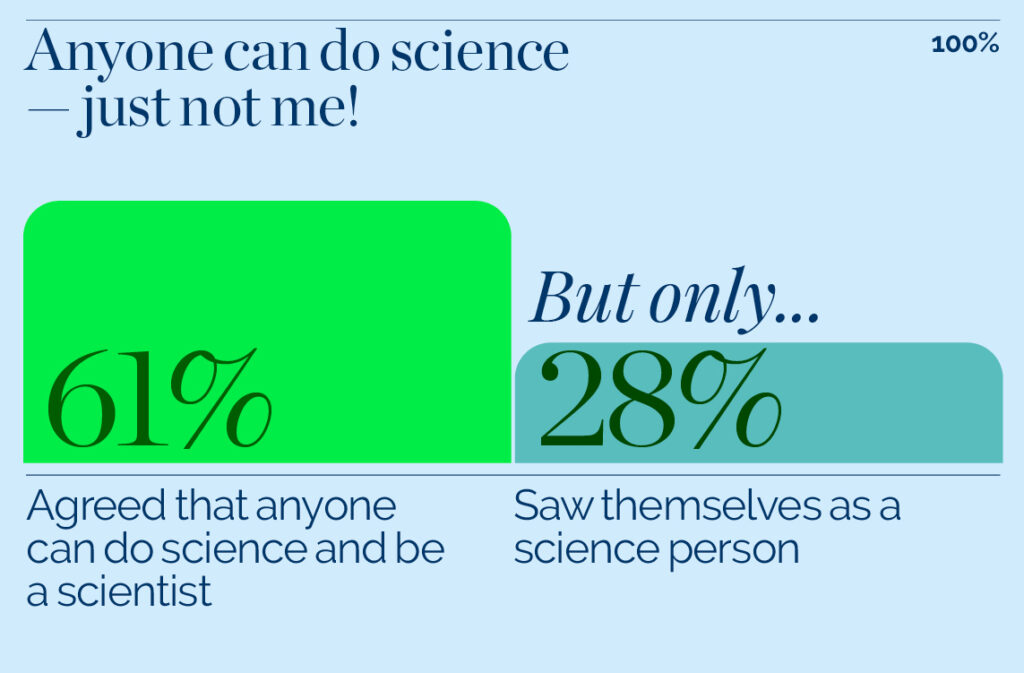

- Clear majorities likewise agreed that STEM is important in making a difference when it comes to global challenges (72%) and at the community level (66%)… but fewer students felt empowered to enact change themselves: 55% agreed that they, personally, could “make a positive difference using STEM.”

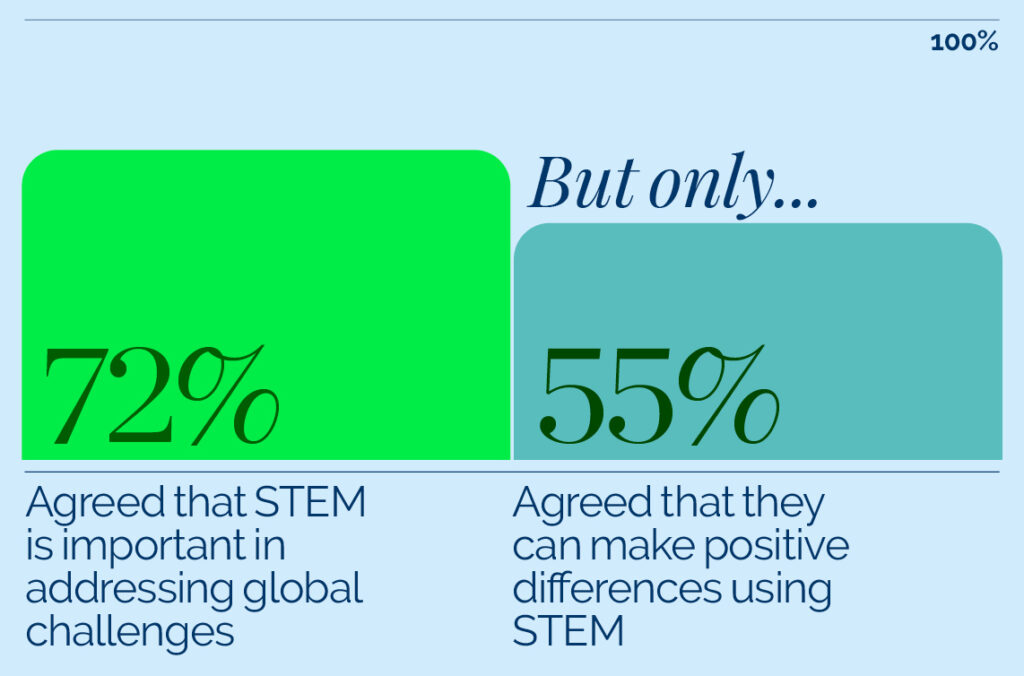

- Two thirds of students (67%) agreed “there are job opportunities in STEM for people with different qualifications and skills” …but only a third (34%) agreed that “people like me work in STEM.” Less than half (44%) believed that “there could be a job” for them in a STEM field.

Young people were more likely to agree on STEM’s inclusivity and importance than with any sense that they could be part of this sector themselves. This discrepancy appears across the cohort but is especially clear among female and disadvantaged students. Only 28% of students saw themselves as a science person, but girls eligible for pupil premium were even less likely to do so (by five percentage points less than boys). When asked whether people like them work in STEM, the least likely to agree were girls (29%) and disadvantaged students (28%).

Young people have long struggled to see themselves as scientists. In the mid-60s, social scientist David Chambers set out to investigate this problem. He asked nearly 5,000 primary school pupils in three different countries to draw a picture of a scientist. Most drew an Einstein lookalike: male, in a lab coat, with glasses and beard, surrounded by books and beakers that suggested mastery over the discipline. Only 28 drew female scientists, and they were all girls.

Chambers’ research showed the power of stereotypical images on young people’s imaginations. Students struggled to see themselves reflected in the ideal scientist, especially if they were female or disadvantaged. Over the following decades, other researchers carried out their own versions of this test, producing a corpus of data over time. Optimistically, pupils’ images have evolved as STEM fields become more diverse, but the balance is still in favour of older men. What’s more, the stereotype tends to become ingrained as children grow up.

Stereotypes matter because they influence what young people choose to do with their lives. While the number of students doing STEM A-levels increased by nearly 20% between 2013 and 2023, the gender balance has barely shifted. Last year, girls were under a quarter of physics A-level entrants and just 15% of those studying computer science. Stemettes, in their recent call for curriculum reform, reveal that the science curriculum for KS3-5 refers 14 times to men—and only once to women or non-binary individuals. There are no references to women or non-binary people in the content for maths, engineering or computer science.

Challenging stereotypes is now on the national agenda. In its 2024 manifesto, the British Science Association has as its first call-to-action to “ensure science in secondary schools is relevant and inclusive to all young people”. Many organisations—including IRIS—are striving to show young people that there is a place for them in the STEM world. But we have more to do for positive messages around inclusivity to have real impact on young people’s choices.

A first step in changing the stereotypical images around STEM would be ensuring that all kinds of students are represented in curriculum content. Another strategy could involve creating more opportunities for young people to meet real researchers like themselves: IRIS has found that students were better able to imagine a future in STEM after meeting researchers, particularly younger scientists working at universities, through our projects.

If young people cannot translate positive impressions of the STEM sector into their own aspirations, these impressions won’t mean much. Only through challenging stereotypes will students actually start to see themselves as potential scientists… and the ideal scientist as someone more like themselves.