Girls can shape our digital future—if only more knew it

Only one in three girls sees computer science lessons as being useful for their future. Far fewer girls are considering a career in tech than boys, even as the sector is booming. What do we stand to lose if young women do not play a role as workers, innovators and leaders in the UK’s digital economy?

By most metrics, the UK’s digital economy is thriving. Our sector reached a combined market valuation of $1 trillion in 2022, putting the UK in the top three tech nations in the world. Key to this success is a vibrant startup ecosystem which innovates in fields as varied as software, cybersecurity and biotech. All this runs on nearly five million skilled workers who ensure we stay ahead of the curve.

However, a well-documented shortage of tech talent undercuts this success story. In September 2023, Gigged.AI, an innovative, AI-powered recruitment platform that links people with tech employment opportunities, published a report on the sector’s talent crisis. They polled 255 decision-makers involved in digital transformation and found that 90% were struggling with skills shortage to some extent. 57% said the situation had worsened since the previous year.

Given this shortage, female underrepresentation in tech is not only disappointing—it is unsustainable. Women make up just around a quarter of the industry’s workers, and only a fraction of its leaders. Besides depriving the sector of much-needed talent, the lack of female tech workers undermines innovation in ways harder to quantify: Whether biotech, artificial intelligence or cybersecurity, new technologies rely on their input to work well, appeal to a variety of users and avoid replicating societal biases.

Girls at school today could play a central role in addressing this shortfall and ensuring the continued success of a strategic sector of the UK’s economy. As it stands, however, the number of girls taking computing-related GCSEs (ICT and computer science) has actually halved over the past eight years. Solving the tech talent shortage therefore starts with a clear understanding of how girls actually relate to computing and technology while in school, including how they differ in their experiences from boys.

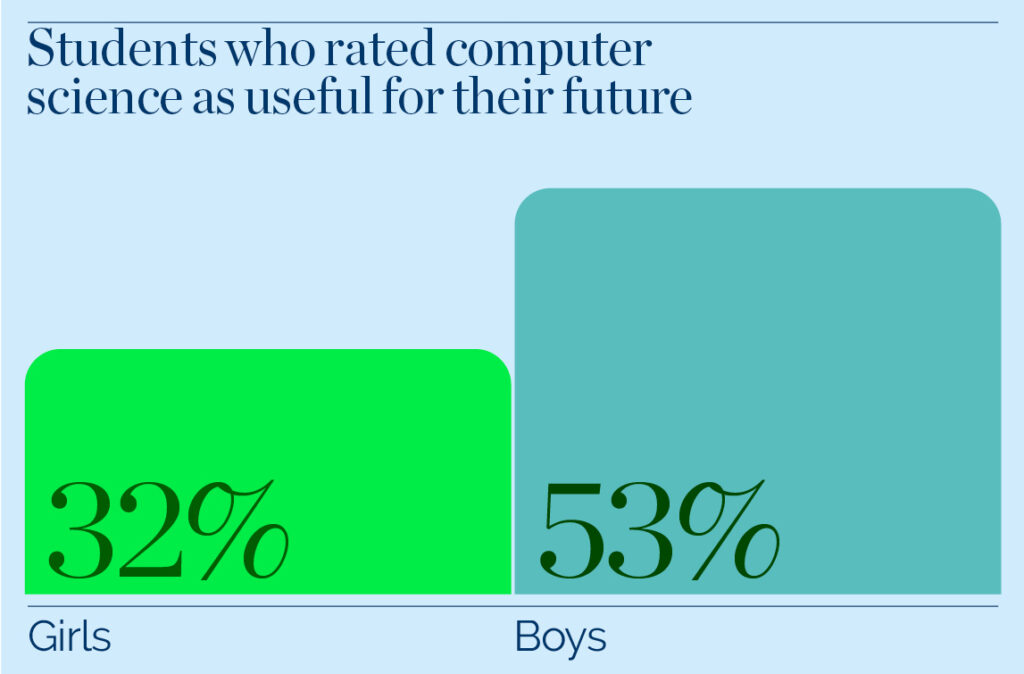

Recently, IRIS conducted a survey of around 2,800 students in year 9, designed to offer schools targeted support in building up their STEM culture with a focus on research and innovation. Girls who responded to our survey were much less likely than boys to think that computer science would be useful for them in the future. Only a third (32%) rated the subject as useful or very useful for their future, compared with over half (53%) of males.

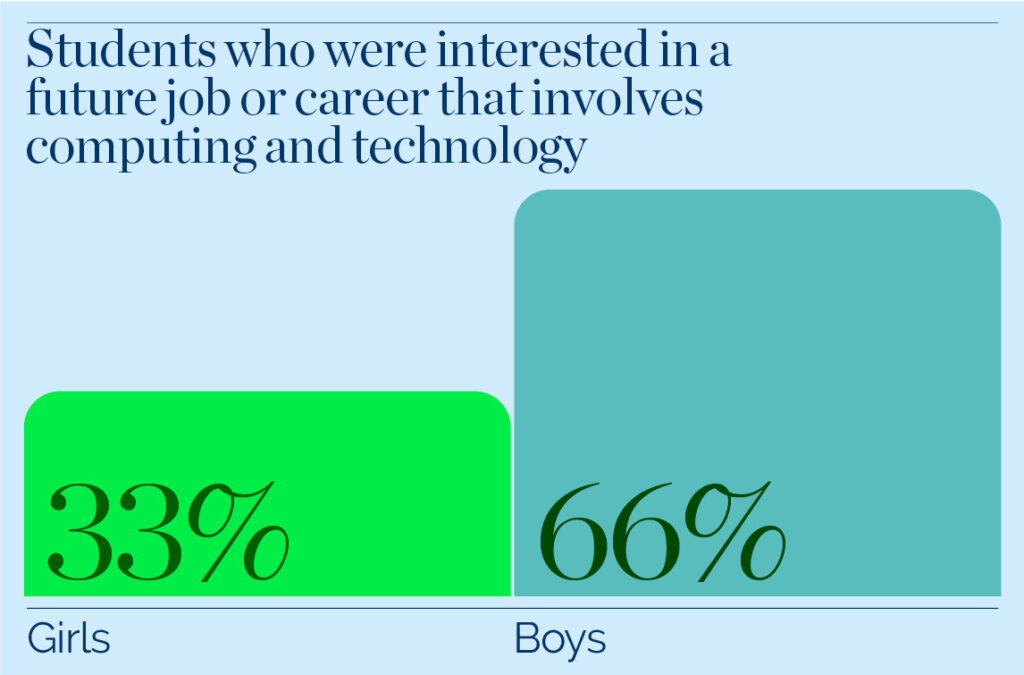

This gender gap widened further when it came to students’ career plans: Exactly a third of female students were interested in jobs involving computing compared to two thirds of males. Even in cohorts that had smaller gender gaps for students’ interest in computer science as a subject in school, the wide gap in career aspirations persisted.

The problem of underrepresentation of women in UK tech, worsening the broader talent shortage that we face, seems to start long before employment itself. It is instead a question of how tech skills are framed for students as they learn them, who they associate with digital work, and what they imagine they could achieve with tech skills.

So why would girls be interested in computing? For starters, salaries tend to be better in appointments that require computer science skills. A software engineer could start out earning £35,296 in 2022, more than other skilled professionals. Digital sector salaries are, on average, 80% higher than in non-tech jobs. There are also plenty of other benefits, such as greater flexibility and skill transferability (after all, it isn’t only tech jobs that need tech skills).

Digital innovation continued throughout the pandemic and was crucial in getting us through that tough period, whether for public information, online shopping or Zoom meetings. Artificial intelligence increasingly takes on certain kinds of work (including coding), but digital skills will remain indispensable to mastering this new technology. Given the demand for skilled labour, attractive returns, and the future-proof nature of innovation, the digital sector will likely be a vector of social mobility for students who enter it.

IRIS’ data suggests that female students in particular need to learn about digital career opportunities from school itself. Rachel McElroy, an industry professional based in Wakefield, put it well in a recent article: when young people are ‘as tech-savvy as they are tech native, why are they experiencing so little exposure to the real-life roles in technology that currently exist? And are we doing enough to support the future of STEM subjects when they’re selecting their GCSE and A-Level options?’

Several organisations are striving to engage young women in tech. Stemettes has been encouraging girls to enter STEM careers for the past decade. Code First Girls and Girls Who Code are among those training young women and enabling them to contribute to high-tech innovation. Computing at School (part of BCS – The Chartered Institute for IT) supports teachers in delivering a relevant, up-to-date curriculum and thus striving to ensure that all young people have an education allowing them to ‘thrive in the digital age’.

At IRIS, we’ve seen incredible things happen when we allow young people to participate in real research and innovation. From using coding and big data skills to help CERN physicists search for new particles to working with satellite data to identify penguin colonies in the Antarctic, authentic application of young people’s digital skills has ignited their passions for science and technology. Engaging more girls in these opportunities is essential to our mission of making sure research and innovation is part of every young person’s experience.

We’ve recently concluded the pilot study of our Research & Innovation Framework, which has involved using student survey data to help schools across the country build dynamic research cultures of their own. As part of a comprehensive and targeted approach, our framework helps schools address the barriers that stand between students and the STEM world as well as show young people real pathways into exciting STEM fields. We look forward to sharing the full findings from our pilot study with you in the coming year.

When it comes to young women and technology, we need to show female students the roles they have to play in the UK’s digital future. This means discussing how innovations impact their lives and giving them first-hand experiences of innovating themselves through technology. It also means showing them the career options open to them and introducing them to other women who are working in, leading and transforming the sector.

Far from being just the end-users of new apps and devices, IRIS wants today’s young women to feel empowered by digital innovation—and know that the future of technology will be shaped by what they choose to make of it.