Talking to Jo Foster on

how to help your students shine at science

In a field that can be prone to more than the odd bit of jargon, Jo Foster is definitely refreshing.

At no point during our meeting does she use educational buzzwords. Instead, she lapses frequently into biological metaphors. Young scientists are “little sprouts,” who need to be nurtured, she says, and there are “swarms” of them in schools.

Endearingly, she then apologises for this, correcting “sprouts” to pupils – yet clearly, it is a sign of how passionate she is about her subject.

Every individual in this country has more science in their back pocket than Newton had in his whole laboratory

Since July, Foster has been the director of Iris – the Institute for Research in Schools – a charity that facilitates groundbreaking scientific research projects in education, aimed at inspiring the next generation of astrophysicists and biochemists.

Before this, she spent her career promoting science in UK state schools, both as a classroom teacher and as the director of a secondary’s science, technology, engineering and maths (Stem) programme for gifted and talented pupils.

She is ardent about equality in education, and ensuring that deprivation does not hold budding researchers back in any way.

As Foster says: “The world at the moment needs scientists, to help solve some of the problems we’ve created.”

THE WORLD NEEDS SCIENTISTS

Throughout the interview, her conversation is wide-ranging and expansive, taking in, among other things, poisonous weever fish, Stormzy’s mic-drop at Glastonbury and an awkward encounter with Richard Dawkins, in which she chased the eminent biologist down a corridor. Dawkins? Really?

As she explains, it was her devoutly religious biology teacher who introduced his writing to her.

“One of my biology teachers was a very committed Christian. And at the time, I was quite a committed atheist. And so we sort of knocked heads a few times, around evolution in particular,” she says.

In spite of this, Foster says her teacher “saw a real interest and enthusiasm for biology in me, keeping her behind one day to give her a copy of Dawkins’ seminal study of evolution, The Blind Watchmaker, which she “devoured” in one night.

“I was so excited about it. It made so much sense to me, and it’s essentially why I chose biology. I was a proper, proper evangelist about Richard Dawkins.”

And so, later in life, while working as a science adviser for a local authority, she attended a conference where he was a keynote speaker. Aged 28, and having drunk two glasses of wine – “I should have known better” – she ended up following him.

“I saw him leave and I sort of chased him down a corridor, saying, ‘Ah, Richard Dawkins! You’re the reason I went into biology! Your books are so fantastic!’

“This poor chap – initially he sort of stood there politely, and then after a while, he just started walking away. I think I was a bit over-enthusiastic – I think he thought I was some sort of a groupie.

“He made a very hasty departure,” she laughs. “Last seen stabbing the lift button. I remember it vividly – he was wearing these mustard-coloured cords.”

ALL CHILDREN ARE SCIENTISTS’

Foster is a dynamic and witty storyteller, but behind the anecdote is an important message – the impact of a good teacher.

“That was the thing – she spotted something in me, she just saw me. You know, that’s what children need, they need to be seen.”

Foster says that while some families will discuss science frequently – as she does with her own children – some will not. And this is where Iris can help the least advantaged pupils, connecting them with genuine researchers in the field. As she says, “all children are scientists”.

“Every parent’s got a story about how their kid smeared Sudocrem all over themselves, or tried to paint the telly – whatever it is, children experiment. And as they grow up through school, they start to understand that this sort of experimenting is called science.

“But, actually, their experience of science in school might not be, ‘wWat happens if I do x or y?’ In fact, if they do that in a science lesson, their teacher will probably say, ‘Well, no, just do the experiment I’ve told you to do.’ And I think sometimes those children lose their excitement.”

Some children do not, of course – she cites one former pupil who studied the behaviour of crows as part of her Extended Project Qualification. Iris helped put her in touch with Professor Nicki Clayton at the University of Cambridge – they engaged in the kind of high-level discussion that might happen between peers in the scientific community.

“She was looking at how corvids problem-solve – they’re really clever; you can see them lifting up bin bags at service stations to get to the rubbish. And she and Nicki got into a real email conversation about it. ‘This is what I found. What do you think, does this chime with your research?’ Nicki said she was really inspired that this work was going on in schools.”

That pupil now studies animal behaviour at university, which Foster says is a mark of how making a personal connection with a scientist can make all the difference.

“Just that contact, sometimes it’s just the moment when you can light a fire for a young person,” she explains.

OUR PROJECTS NED TO SPARKLE

Like many teachers, there is something of the actor about Foster. She describes the recently launched Iris database – on which pupils can look up researchers to help with their projects – as a kind of mystical portal, dispelling stereotypes of lofty, inaccessible academics.

“Every individual in this country has more science in their back pocket than Newton had in his whole laboratory,” she says. “We’re absolutely inundated with science and technology. But I think sometimes there’s a sense of, ‘Oh, they’re scientists – they’re not with us.’ We need to break that down.

“I imagine the Iris portal as a massive set of wooden doors, where the student knocks and the door creaks open.”

She mimes a tentative knock, mimics the sound of an ancient door whining on its hinges – “The student says, ‘I need someone who’s an expert in woodlouse foraging,’ and they say, ‘Ah, yes, we know just the person,’ and the doors open wide to serried ranks of golden academics, glowing.”

She pauses, laughing – “Obviously it’s not really like that. It’s a database.”

However, for Foster, Iris is not only about inspiring pupils who already have a passion for the subject, but also recovering the untapped potential of pupils who may have lost that initial enthusiasm.

“All of our projects have a thing that I call the sparkle test. I see it as like a bauble on a Christmas tree – it has to be exciting.”

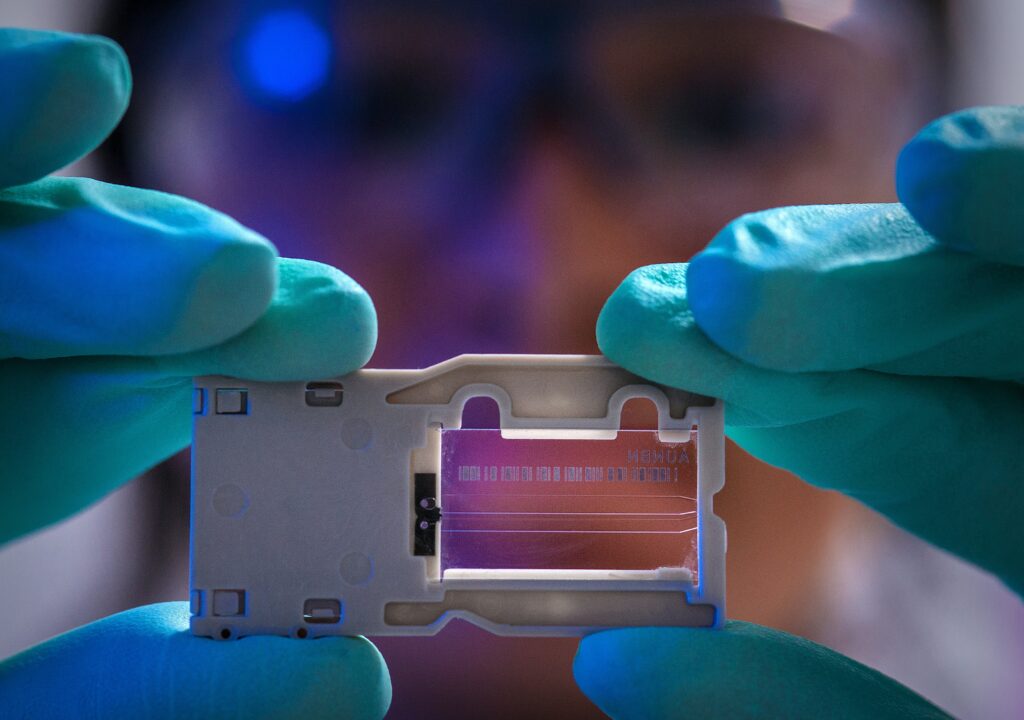

For example, one IRIS project she recalls, from when she was director of a specialist Stem programme at Camborne Science Academy, involved a live stream of data from the International Space Station.

“It was when [astronaut] Tim Peake was there, and obviously he was a bit of a hero. We got a detector, which was the same type that they use in CERN in the Large Hadron Collider. I thought, ‘I’m not going to need to sell this, I’ll put up a poster and the kids will come’ – and they did.”

More recent projects have involved pupils identifying anomalous objects in space picked up by the James Webb Space Telescope, or even splicing the genome of the human whipworm.

Helping pupils with projects of this kind also enables their teachers to rediscover a love for their subject.

“At Iris we came up with this phrase ‘teacher-scientist’, where they are teaching but also engaged in this really novel piece of research. One of our catchphrases is that this is science where the answers are not in the back of the textbook,” says Foster.

This focus on real-world research is important to her. One of the stereotypes she certainly dispels is that of the white-coated scientist marooned in their lab.

As a trustee of the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford, she talks proudly about one of its recent acquisitions – the microphone that Stormzy dropped during his set at Glastonbury.

“It has all the dents in it. Some people might think of a museum as something that is stuck in the past, but they had the foresight to think this was a really important moment,” she says.

And for her own biology A level, Foster spent one summer studying the impact of pig manure on succession – not the fraught family dynamics of media dynasties, but the process by which ecological species change over time.

She describes how she “traipsed around the fields at school looking at vegetation” and it was at that moment she realised “this is what actual scientists do”.

“It felt like it gave me an insight into what it might be like. Just a little insight, a glimmer of it. And that’s what we’re trying to bring to the children who are involved with us now.”

Her focus on research in the field – literally – continued during her PhD at the University of York, when she studied how planting different species of trees impacted biodiversity, spending “two years tromping around woodlands counting things to get any sort of data that was realistic”.

Her work coincided with the European Union’s set-aside scheme, whereby farmers were required to leave some of their land as natural woodland.

“It was the time of European butter mountains and milk lakes – I still really, really wish those were real things,” Foster laughs. However, she realised that many farmers were using the “woodland” to plant Christmas trees for sale.

“They found a loophole,” she says. “My children are the same – curious minds!”

GETTING INTO TEACHING

Foster’s conclusions were subsequently included in the guidance for the management of farm woodlands. Making a difference, and the close study of one’s immediate environment, are concerns that have coloured her teaching style ever since.

Her own pathway into teaching came about, she says, largely by “accident” – she had recently completed her PhD, and her own former school, an independent girls’ school, had been let down at the last minute by a new biology appointment.

“They didn’t use the words ‘we’re desperate’,” she laughs self-deprecatingly, “but…

“Obviously it was a bit odd, because I was used to stopping at the staffroom door, and now I was allowed to walk in. But also, it was really helpful because, of course, you see yourself a bit in the students that you teach, even more so if you’re back in some of your old classrooms.”

Her lessons sound like enormous fun. One lesson in Cornwall involved teaching antibodies through pupils dressing up in suits with Lego blocks attached – they had to find their matched pair by attempting to connect the bricks. A former pupil recently reminded her of this in Sainsbury’s.

Foster is an animated, thought-provoking speaker and it is clear she is a born teacher, although she humbly describes her time in the profession as an “enormous privilege”.

Two experiences prepared her well for her time in the classroom – at university, she ran a sports club for children with special educational needs, and she also spent time as a caretaker in a sheltered workplace for adults with additional needs – “washing pots while singing songs from the musicals”.

“It just made me very comfortable, you know – whatever goes on, your lessons, whatever happens, it’s not going to be as extreme as someone throwing a pot of water at you while singing ‘the sun will come out tomorrow’.”

She later became the special educational needs coordinator at one of her schools, and she says that for her, the mark of a good teacher is “seeing the spark in each child and nurturing it”. “You may have a tide of children coming in and out, but you have to connect with each one,” she adds.

WE’VE GOT THESE CHILDREN HIDDEN IN EVERY SCHOOL IN THE COUNTRY

After a brief stint teaching at a prep school in York, she has lived in Cornwall for most of her career, working in the state sector. The local environment has prompted a range of research, she says.

One recent Iris project involved pupils investigating a common scourge of the South Coast – weever fish.

These poisonous fish hide under the sand, yet have venomous protruding spines. If children step on these, the stings are extremely painful, and the treatment is even worse – you pour very hot water over the foot to deactivate the venom.

Combining data from Iris on climate change with figures from the Royal National Lifeboat Institution on weever fish, pupils designed an app for parents, informing them of the likely danger from the fish at different times and temperatures.

“It’s about children taking what they’ve learned and applying it to their local environment,” says Foster. “Most children really love being outdoors.

“This particular group of students won a prize at a science fair in Korea for the most innovative piece of research, and they were 17 when they won.

“And they were children from a state school in quite a deprived area. So we’re not just talking about the most academically elite children – we’ve got these children hidden in every school in the country.

“Part of what I’m interested in is helping schools or teachers to winkle them out and let them really shine – to understand what science really is, that there’s a lot of really, really cool stuff you can do with it.”