Plastic, worms and flies.

Students explore science on a microscopic scale

Secondary students from around the country have been taking a closer look at their research subjects using an instrument more commonly found in leading universities, research organisations and high-tech companies than schools. The Scanning Electron Microscope is capable of much higher magnifications than a light microscope, allowing researchers to see extremely small objects, such as the surfaces of cells and organisms, in incredibly fine and precise detail.

The instrument has been loaned to secondary schools around the country by manufacturers Hitachi High-Tech in partnership with the Natural History Museum, the Royal Microscopical Society and the Institute for Research in Schools. The SEM has enabled students to engage in their research in an exciting and immersive way.

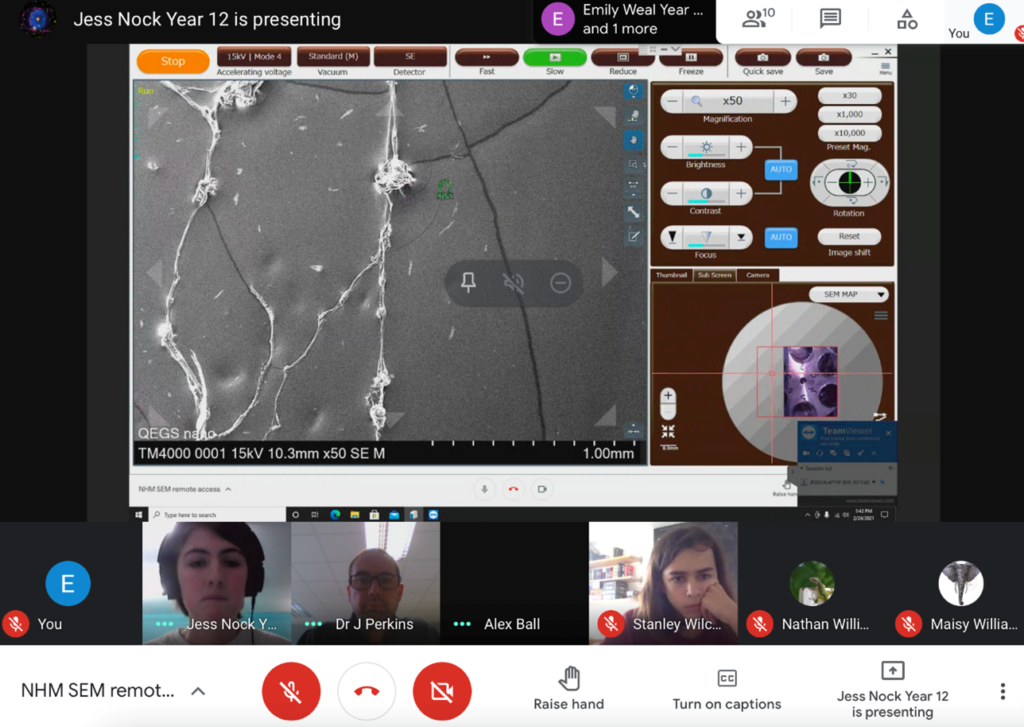

Students share their findings during lockdown using the Natural History Museum’s SEM remotely

Students share their findings during lockdown using the Natural History Museum’s SEM remotelyHere’s what two schools have been investigating

How to make nanofibres

Students from Queens Elizabeth’s Grammar School used the SEM to investigate cellulose nanofibres (CNF) – a pseudo-plastic mostly produced from wood pulp. Although the fibres are not visible to the human eye, the SEM allows the students to clearly identify the structure. The students have ambitions to create their own CNF.

When lockdown hit, students assumed research would pause, however Alex Ball, Head of Division, Imaging and Analysis at the Natural History Museum, set-up remote microscopy sessions for the students allowing them to control the SEM virtually.

“Alex coated the samples to figure out the best imaging conditions for the CNF. This was the first use of the remote operation facility of the SEM and we were in full control from our homes.” said James Perkins, head of the schools science faculty.

The whole experience has helped us explore good scientific practice n setting up our own practicals. It has also taught us about the ethics of working with small organisms as well as communication, teamwork and leadership skills.

Building a fruit fly colony

While many people google ways to rid their house of fruit flies, Lara, Year 11, and her school mates at Queen Elizabeth’s Grammar School in Kent decided to start a colony of them. Fruit flies are interesting because they share 75 per cent of the genes that cause disease in humans. They also reproduce incredibly fast.

Lara and her crew started by exploring the flies’ anatomy, the structure of their eyes and mouth. Once they mastered the SEM, they learned to dissect the tiny insects using its high magnification.

“We became very interested in the food preferences and digestive system of the flies. Dr Jerome Korzelius at the University of Kent gave us valuable information and advice about dissection techniques and how we could manage it with our school equipment,” said Lara.

They eventually researched how to aid reproduction to begin building the colony.

“We first learned to sex them (easier said than done), then experimented with genetic crosses to demonstrate inheritance,” said Lara.

The students successfully colonised fruit flies. The process not only taught them about the biology of fruit flies, but allowed them to build their microscopy and research skills and much more.

“The whole experience has helped us explore good scientific practice in setting up our own practicals. It has also taught us about the ethics of working with small organisms as well as communication, teamwork and leadership skills,” commented Lara.

Plastic lunch: young researchers place mealworms on styrofoam

Plastic lunch: young researchers place mealworms on styrofoamCan mealworms digest plastic?

Further north, year 9 students from Liverpool Sciences UTC, known as the Real Meal Group, have been studying mealworm larvae under the SEM to investigate the digestive abilities of the animal. Their research could potentially provide a solution to one of humanity’s greatest environmental challenges.

So far, the young researchers have found traces of microplastic waste in the gut of mealworm. But they want to understand what proportion of the plastic waste is digested into harmless substances – previous research suggests it can be up to 50 per cent. Following their own research, the students are looking to produce a household plastic waste digester box that uses mealworm to break down non-recyclable plastic waste. Two students are designing the box itself using CAD software Autodesk Fusion 360 and they will use some of the data collected from their research to inform the design decisions.

Another student is looking into how people could access the box remotely and monitor and make changes from their smart phones. He is now focusing on the more technical aspects of this new challenge. Namely, how to connect a series of sensors to a microcomputer to monitor conditions in the digestor box and trigger heaters and fans to maintain temperature and humidity within optimal ranges for the mealworm.

Niamh, Year 12, director for the Baltic Research Institute (BRI) – the first student-led research institute in the UK, says:

“The Year 9 students’ study presents an alternative and responsible way of disposing of our plastic waste, which would be extremely beneficial in terms of reducing the effects of climate change.”

Students also used the SEM to investigate hygiene standards within the college during the pandemic, examining door handles, light switches and sinks for dirt and microbes and identifying a suspected fungal colony on a keyboard.

Charlotte, year 12, said: “The SEM has given us opportunities for learning new skills and to gain experience for university. We have been able to use it for our Extended Project Qualifications (EPQs) and start our own independent research projects, which has been really interesting and has inspired new research-based EPQs.”